- Joined

- 01.05.24

- Messages

- 251

- Reaction score

- 5,251

- Points

- 93

We create accounts online such as Facebook, Instagram, ext. and we need to secure them from being exploited. We shall look into securing our accounts on the Internet or online.

It has been suggested that the strongest password is the one you don’t know. Humans are notoriously poor at developing effective passwords because we are limited largely by the constraints of memory and the desire for convenience. Later

in this chapter I will teach you how to create effective, difficult-to-crack passwords that are still memorable and usable. I recommend you use a different username and password on all of your online accounts. This may seem terribly difficult,

exceedingly inconvenient, and impossible to remember, and generally I would agree. With only the benefit of human memory it would be nearly impossible to

remember and use more than just a few passwords of the recommended length

and complexity. For that reason, I’ve chosen to begin this chapter with a discussion of password managers, one of the single biggest and most important tools you can

employ to strengthen your digital security posture.

I have been using password managers for years, and there’s no way I’d even consider the possibility of going back to not using one. A password manager is a purpose-built application that creates an encrypted database for storing and organizing your usernames and passwords. Password managers solve many of the problems inherent in password development and use by “remembering” your passwords for you so that you don’t have to. This allows you to easily implement the online account best practices of using a different username and password on every one of your online accounts, using passwords that are randomly generated and of the maximum allowable length and complexity, and changing them as often as you deem prudent without fear of forgetting them.

Because password managers store all your passwords in one place, they create an “eggs-in-one-basket” situation. It should go without saying that a password

manager should be protected by an extremely strong password, and if at all possible, two-factor authentication (2FA). If you can only take the time to remember one

very strong, very complex password, you should do so for your password manager. Be especially careful not to lose or forget this password.

Password managers are designed to not let you back in without the correct authentication credentials. This could result in the loss of all passwords for all your accounts, an unenviable situation in which to find yourself. It should also go

without saying that your password manager should be backed up, frequently. If you are using a host-based manager and your computer crashes, you must have a

way to recover the information the password manager contained. Otherwise you risk being locked out of, and potentially losing, hundreds of accounts.

There are two basic categories of password managers, host-based and web-based. Although I will discuss both, my recommendation is to only use host-based

password managers. While web-based password managers are strongly encrypted, they are significantly riskier because they store your passwords in the cloud on machines that you do not personally control. Further, online password databases are a natural target for hackers because of the wealth of information they contain.

Though a certain amount of confidence is placed in all online account providers, an extraordinary amount is required to entrust your passwords to all your accounts to

an online service. I have not found yet an online service to which I am ready to give this level of trust for my extremely sensitive accounts, and frankly don’t believe I ever will.

This is somewhat less convenient than a web-based password manager as your passwords are only available on your computer or device. As a result, you may not

be able to log into your online accounts from computers other than the ones you own and that store your password database. This is not an issue for me since I’m

reluctant to log into an account from a computer that I don’t control and therefore don’t trust. However, there are good reasons to use a host-based password manager. The biggest advantage host-based managers enjoy over web-based

password managers is security. I have an instinctual, inherent distrust in cloud storage, and prefer to keep all my password, stored safely on my own devices .

QUBES OS: KEEPASSX

KeePassX is by far my favorite open-source host-based password manager for Linux machines, and it comes pre-installed on Qubes, on the Debian VMs. I recommend you create a new database on a VM labeled “vault” with KeePassX,

and to further enhance your security, store that database inside a hidden veracrypt container with a strong password. It’s as simple as downloading the .tar.bz2 file from the veracrypt website, decompressing it, and running a bash command on the folder to install veracrypt. If you’re having difficulty doing this, feel free to contact me and I will help you with that.

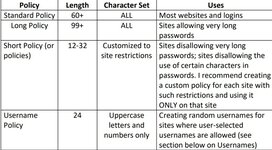

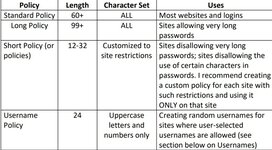

GLOBAL PASSWORD POLICIES

overlooked in the discussion of online security. I think this is a huge mistake. I believe that usernames should be considered the very first line of defense for such accounts. Most websites require at least two things to log in: a username and a

password. If the attacker cannot find your username, your account I significantly more secure. To launch an attack against your account would require first finding your account and an obscure username greatly reduces the chances of this

happening.

A predictable username has several problems, the first of which is susceptibility to guessing. If an attacker is targeting an attack against a specific individual, he or she will attempt to guess the target’s username(s) to various sites. The attacker will base guesses on known information about that person. This information can be gathered online from social media sites, personal blogs, people search sites, and public records. Predictable usernames are most commonly generated from a

combination of first, middle, and last names. For example, if your name is Amy Schumer your username might be “ABSchumer”. Sometimes they are combinations of monikers or initials and dates of birth such as “chumer81”. Once

the username has been discovered the attacker can now target that account and attempt to break the password. Conversely, the attacker can never begin targeting the account if it cannot be located.

The second problem with predictable usernames is that they are typically used across multiple websites, especially when the email address associated with the

account is used as the username. Using the same username across several of your accounts correlates those accounts. This makes them easier to locate and leaks

information about you such as your social media presence, interests, the online services and commerce sites you use, etc. This can expose a great deal of information about you. After locating your username, the attacker in this scenario

may use a service like Namechk (https://namechk.com/) to locate other accounts you have. If a common username and password combination are used across

multiple accounts, hacking one account can very quickly lead to the compromise of multiple accounts with disastrous consequences. Though you may not care if your throwaway email account or an old social media profile is hacked, it could lead to

your bank account or an active e-commerce account being hacked if they share a username and password.

The third major problem with predictable usernames is that when breaches occur, the username and password combinations are usually sold or posted online in massive databases. If you use a username or email address that correlates to your name, a breach can reveal personal information about you, especially if you have an uncommon name. As an example, let’s assume your name is Harrison Tang and your username to a site is harrisontang83, an obvious and easily guessable username based on your name and year of birth. Let’s also assume that a large

password breach occurs at a given site, and the usernames and passwords are posted online (which is very common by the way). Anyone seeing this database

would easily recognize your name and with some research could probably confirm the user is you. This reveals information about you and your personal interests. This could be a dating site (like Adult Friend Finder or Ashley Madison), a bank, an ecommerce site, or an online service of some sort. This would reveal to anyone

seeing this database that you use this dating site, bank, online retailer, or service,leading to further avenues of exploitation.

To combat this, you should consider the username a security measure. If the usernames on your accounts happen to be obvious, change them immediately. If a particular site does not allow you to change your username, consider closing the account and opening a new one using a non-obvious username. I’d personally consider a random-generated username for maximum anonymity. An ideal username would look something like this: 532T4VYL9NQ54BTMDZI1.

compromise of all of your sensitive data. For this reason, you need to know how to develop a strong password that you can remember and enter manually.

PASSWORD BASICS: Before I discuss how to build a good, strong password it is critical to understand what comprises one. There are two factors that make (or break) a password: length and complexity. Added length and complexity both

exponentially increase the difficulty in breaking a password. Password length is uncomplicated. With today’s computing power, 20 characters is a prudent MINIMUM length (if your site does not allow a longer password). When passwords are cracked using brute force techniques, powerful processors run through hundreds of millions or billions of possible passwords per second. Every possible combination of a very short password could be tested in a matter of minutes with strong enough computing power, and computers are growing faster

every day. Password length is the single most important factor that increases the strength of a password. When using a password manager, we will use passwords that are much longer than 20 characters, sometimes exceeding 100. If this seems like overkill, consider the following. Regardless of whether a password is 1 character or 100, both

require the exact same amount of effort when using a password manager. Why not go with the longest allowable password? If a site with which you are registering does not allow a longer password, think twice before registering with

that service.

Complexity can be a bit trickier. Password complexity is created by following some basic rules. Ideally a password will contain characters from the full ASCII suite, including upper and lower-case letters, numbers, special characters

(!@#$%^&*_+=-/.,<>?;””:[]}{\|), and spaces. Spaces are very important as they are not commonly used in passwords, and as a result are not commonly searched for by password-cracking programs.

PASSWORD VULNERABILITIES: You may be wondering why such extreme measures are needed to develop an effective password. The reason complexity is desirable is that passwords are not typically cracked by “dumb” brute force methods alone, like starting at lowercase “a” and going all the way through “ZZZZZZZZZZZ”, and testing everything in between.

Though brute-force attacks exist, they are not the most popular or effective method of cracking a password, as they can take an immense amount of time. Time is the enemy of the password cracker, and your goal in designing a password should not be to make it unbreakable. Nothing is truly unbreakable given enough

time, but you should aim to make it take an unacceptable length of time.

Passwords are usually cracked in a much timelier manner by understanding how

people make passwords and designing a dictionary attack to defeat it. Dictionary

attacks rely on specific knowledge of the target and heuristics.

Knowledge of the target is useful when cracking a password because personal information is frequently used as the basis for human-generated passwords. An individual may use his or her birthday (or birthdays of a spouse, or children, or a combination thereof), favorite sports team or player, or other personal information or interests. This information can be input into programs like the Common User Password Profiler (CUPP). This application takes such tedious personal data as birthdays, names, occupation, and other keywords, and generates thousands of potential passwords based on the data. This list of passwords can then be programmed into a custom dictionary attack against the target machine or account.

Dictionary attacks work through a trial and error approach. First, a list of passwords is entered into a password-cracking program. This list might be customized against the target (through applications like CUPP as described above), or it may be more generic. Even though “generic” lists are not tailored to a specific target, they are still far more successful than they should be. These lists are based upon the heuristics of how people develop passwords. These lists are developed with the knowledge that many people use the techniques explained in the following list of password pitfalls.

o Never use a dictionary word as your password. Almost all dictionary attacks will include a list of dictionary words in a number of languages.

o Do not use a dictionary word with numbers/characters at the beginning or end (e.g. password11 or 11password), and do not use a dictionary word with simple obfuscation (p@ssword). These are the most common methods of adding complexity to a dictionary word-based password, and combinations such as these would be tested in any decent dictionary attack.

o Never leave the default password on your devices (Bluetooth devices and wireless routers are notable offenders in the retail market). Default passwords for any device imaginable are available through a simple web search and would absolutely be included in an attack against a known device.

o Never use information that is personally relatable to you. As I have discussed, information that is personally relatable to you can be used in an attack that is customized to target you specifically.

The inherent problem with complexity is that it makes our passwords difficult to remember, though with creativity it is still possible to create passwords that are very long, very complex, yet still memorable. Below are two of my favorite techniques to develop strong (and memorable) passwords.

THE PASSPHRASE: A passphrase is a short phrase instead of a single word and is my preferred technique. Passphrases work like passwords but are much more

difficult to break due to their extreme length. Additionally, if appropriate punctuation is used, a passphrase will contain complexity with upper and lower-case letters and spaces. A shrewd passphrase designer could even devise phrase

that contains numbers and special characters. An example of a solid passphrase might be the following.

“There’s always money in the banana stand!”

An even better example might be:

“We were married on 07/10/09 on Revere Beach”.

Both of those passphrases are extremely strong and would take a long, long time to break. The first one contains 43 characters, including letters in upper and lower-cases, special characters, and spaces. The second is even longer at 46 characters, and it contains numbers in addition to having all the characteristics of the first. Additionally, neither of these passphrases would be terribly difficult to remember.

DICEWARE PASSPHRASES: Diceware is a method of creating secure, randomly-generated passphrases using a set of dice to create entropy. To create a diceware passphrase you will need one dice and a diceware word list. Numerous diceware word lists are available online. Because of the way passwords are created, these lists do not need to be kept secret. These lists consist of 7,776 five-digit numbers, each with an accompanying word and look like this:

43612 noisy

43613 nolan

43614 noll

43615 nolo

43616 nomad

43621 non

43622 nonce

43623 none

43624 nook

43625 noon

43626 noose

After you have acquired a dice and a word list, you can begin creating a passphrase by rolling the dice and recording the result. Do this five times. The five numbers that you recorded will correspond with a word on the diceware list. This is the first word in your passphrase. You must repeat this process for every additional word you wish to add to your passphrase. For an eight-word passphrase you will have to roll the dice 40 times. Diceware passwords are incredibly strong but also enjoy the benefit of being incredibly easy to remember. A resulting diceware passphrase may look like the following. puma visor closet fob angelo bottle timid taxi fjord baggy Consisting of ten short words, this passphrase contains 58 characters including spaces and would not be overly difficult to remember. After you have completed this and compiled the words from the list into a passphrase you can add even more entropy to the passphrase by capitalizing certain words, inserting numbers and special characters, and adding spaces. Experts currently recommend that six words be used in a diceware passphrase for standard-security applications, with more words added for higher-security purposes. You should NEVER use a digital or online dice-roll simulator for this. If it is compromised or in any way insecure, so is your new passphrase. Wordlists are at https://theworld.com/~reinhold/diceware.html

THE “FIRST LETTER” METHOD: This method is a great way to develop a complex password, especially if it does not have to be terribly long (or cannot be because of site restrictions on password length). For this method select a phrase or lyric that is memorable only to you. Take the first (or last) letter of each word to form your password. In the example below, we use a few words from the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States. We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility

This password contains 20 characters, upper and lowercase letters (the letters that

are actually capitalized in the Preamble are capitalized in the password), and does not in any way resemble a dictionary word. This would be a very robust password. The complexity and length of this password could be increased greatly by spelling out a couple of the words in the phrase, and more complex still by replacing a letter or two with special symbols as in the following example.

Containing 51 characters, this is the strongest password yet, but would still be fairly easy to remember after taking some time to commit it to memory. The first seven words are spelled out and punctuated correctly, and the last fifteen words are represented only by a first letter, some of which are substituted with a special

character of number. This password is very long and very complex, and would take EONS to crack with current computing power.

MULTIPLE ACCOUNTS: Though this is covered elsewhere in this book it is worth reiterating. Each of your online accounts should have its own unique password that is not used on any other account. Otherwise the compromise of one account can lead quickly to the compromise of many of your accounts. If a password

manager is doing all the work for you there is no reason not to have different passwords on every single online account.

PASSWORD RESET MECHANISMS: Most online accounts feature a password

recovery option for use in case you forget your password. Though these are sometimes referred to as “security” questions, in reality they are convenience questions for forgetful users. Numerous accounts have been hacked by guessing

the answers to security questions or answering them correctly based on open source research, including the Yahoo Mail account of former Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin. The best way to answer these questions is with a randomly

generated series of letters, numbers, and special characters (if numbers and special characters are allowed). This will make your account far more difficult to

breach through the password-reset questions. If you use a password manager, the answers to these questions can be stored in the “Comments” section of each

entry, allowing you to reset your password in the event you become locked out of your account.

If you are prompted to enter a password “hint”, I recommend using purposely misleading information. This will send the attacker on a wild goose chase if he or she attempt to discover your password through the information contained in the hint. You should never use anything in the hint that leaks any personal information

about you, and if you are using a strong, randomly generated password, the hint should have nothing at all to do with the password itself. Some examples of my favorite purposely misleading hints might be: My Birthday, Miami Dolphins, Texas Hold’em, or Password, none of which have anything at all to do with the password at which they “hint”.

PASSWORD LIFESPAN AND PASSWORD FATIGUE: Like youthful good looks,

architecture, and perishable foods, passwords are vulnerable to the ravages of time. The longer an attacker has to work at compromising your password, the

weaker it becomes in practice. Accordingly, password should be change periodically. In my opinion, they should be changed every six months if no extenuating circumstances exist. I change all of my important passwords much

more often than that, because as a security professional, I am probably much more likely than most to be targeted (not to mention much more paranoid, as well). If you have any reason to suspect an online account, your wireless network, or your computer itself has been breached you should change your password IMMEDIATELY. The new password should be drastically different from the old one.

If you are using a password manager, a practice I strongly recommend, changing passwords is not difficult at all. Remembering them is a non-issue. If you choose not to use a password manager, or you have more than one or two accounts for which you prefer to enter the password manually, you may become susceptible to password fatigue. Password fatigue is the phenomenon of using the same four or five passwords in rotation if you change them, or are forced to change them, frequently. This impacts security negatively by making your password patterns predictable, and exposes you to the possibility of all the passwords in your rotation being cracked.

With modern password hashing techniques, changing passwords frequently is typically unnecessary. The corporate practice of requiring a new password every 30, 60, or 90 days is a throwback to the days when passwords were predominantly stored in plaintext and there was significant risk of the entire password database being hacked. If passwords are being stored correctly, they should be secure even when the database is breached. With that being said, I am more paranoid than most and regularly change my passwords on all of my important accounts. Though it takes a bit of time and patience to update passwords on multiple sites, doing a few each week in a constant rotation can ease the tedium a bit and ensures that if one of your passwords is compromised it will only be good for a few weeks at most.

to the compromise of several of his accounts. Passwords are becoming a weaker method for securing data. Passwords can be brute-force, captured during insecure

logins, via key-loggers, via phishing pages, or lost when sites that do not store passwords securely are hacked. There is a method of securing many accounts that offers an orders-of-magnitude increase in the security of those accounts: two-factor authentication(2FA).

Using 2FA, each login requires that you offer something other than just a username and password. There are several ways 2FA can work, and there are three categories of information that can be used as a second factor. The three possible factors are something you know (usually a password), something you have, and something you are (fingerprint, retinal scan, voice print, etc.). A 2FA scheme will utilize at least two of these factors, one of which is almost always a password.

PGP KEY MESSAGE DECRYPTION: With your account setup with a PGP key that you control setup as a second factor, you will enter your username and password to login. Before being allowed access to the account, you will be presented with an encrypted message, that was encrypted with your own PGP public key. Once you decrypt the message, a code will be given to you. Upon entering the code, access to the account will be granted.

Sadly, I have yet to seen a Clearnet website deploy this kind of security measure. The only websites that have this kind of protection in place are darknet websites and markets. Most likely because of the fact that most people don’t use PGP to communicate, if not on the darknet, so it is not a very popular security measure.

This is very unfortunate, as PGP key message decryption, is most likely the single best method to secure your account from hackers, and currently, my favorite.

With Qubes OS, we can create an isolated VM, with no access to the internet, especially designed for the use of PGP, which makes things extremely more secure.

I recommend you clone the fedora-26 TemplateVM into fedora-26-pgp and then simply create a new AppVM based on that template, to which you will then label it “pgp” and give it no access to the internet. From there, to use PGP it is as easy as setting up a new key pair and knowing the command line commands to

encrypt/decrypt messages. You can follow the tutorial in the link below to accomplish so.

https://apapadop.wordpress.com/2013/08/21/using-gnupg-with-qubesos/

TEXT/SMS: With this method, a code will be sent via text/SMS message to your

mobile phone. Upon entering the code, which is typically 6-8 digits, access to the account will be granted.

Using the text/SMS scheme of two-factor authentication is a major security upgrade but is not as good as the next option we will discuss: the dedicated authenticator app. Text/SMS can be defeated if your phone’s texts are forwarded to another number. This may happen if your service provider account is hacked, or if a phone company employee is a victim of social engineering and allows an unauthorized person to make changes to your account. This may seem like a very sophisticated and unlikely attack vector, but several well-documented cases of this

attack have occurred.

APP (APPLICATION): Another option for smartphone owners and Qubes OS users is a dedicated two-factor authentication app. One such app is the Google Authenticator. Others include

2FAS

FreeOTP

Aegis

With the app installed, you will visit the website and enter your username and password. Then, you will open the app, which will display a six-digit, one-time code for that account (this code changes every 30 seconds). You will enter the one-time code to login. Setup for the app is slightly more complicated than setting up text/SMS, but it is far from difficult.

Once the app is installed on your computer/phone, you visit the site for which you wish to setup 2FA. The site will give you a code that you can input on the app, which links your phone/computer to the account, and adds an entry for the

account into the app. Google Authenticator works for a number of sites, including Amazon Web Services, Dropbox, Gmail, Facebook, Microsoft, Wordpress, and more...

Though I generally consider app-based tokens more secure than text/SMS systems, it is important to be aware that they are not invulnerable. While an attack on your phone could get some of your login tokens, the capture of the token that is transmitted to your app could allow an attacker unlimited access to all your two-factor codes indefinitely. This is very unlikely however. In Qubes, you should create a VM specifically for this purpose ALONE, don’t use for nothing else, and don’t download or navigate the web in that VM. There are other VMs you can create specifically for those other purposes. Below is the link to a tutorial in setting up a VM on Qubes for this purpose.

https://www.qubes-os.org/doc/multifactor-authentication/

COMMON TO ALL: BASIC BEST PRACTICES

DO YOU REALLY NEED AN ACCOUNT? Many online accounts that you are asked to create are unnecessary and time-consuming. Some services require an account. Before you set one up, I strongly recommend considering the potential downsides. You should also carefully consider what data you are willing to entrust to a website. An online dating site may request a great deal of data and periodically, invite you to participate in surveys. Of course, it will also ask you to upload photographs. I urge you to use caution when doing so because it is a near certainty that any information you put on the internet will one day be compromised in some manner.

USE ACCURATE INFORMATION SPARINGLY: When signing up for a new online account, consider what information is really important and necessary to the creation of the account. When you sign up for an email account, does it really need your true date of birth? Obviously not. E-commerce sites require your address to ship packages to you, but do they need your real name? Perhaps they do. When you create an online account with your bank, do you need to use complete and accurate information? Yes, you most likely do, unless you are conducting any type of fraudulent activity.

CHECK THE STATUS OF EXISTING ACCOUNTS: An early step in securing online accounts is to ensure they have not been breached. There are a couple of services that will offer you a bit of insight into this by allowing you to cross-reference your email address against lists of hacked accounts. Breachalarm.com allows you to input your email address, which it then cross-references against a list of hacked accounts. If your account has been hacked, change the password immediately.

Haveibeenpwned.com is a similar website that checks both email addresses and usernames against lists of known-hacked accounts. The site is relatively new and maintains a database of breached accounts.

GET RID OF UNUSED OR UNTRUSTED ACCOUNTS: If you have old online accounts

that are no longer used, close them down if possible. Some websites can help you do this such as, AccountKiller(www.accountkiller.com), and Just Delete Me(

www.justdelete.me). Before closing an account, I highly recommend you get rid of as much personal information as you can in the account. Many services will continue to harvest your account for personal information, even after it has been closed. Before closing the account, login and replace the information in as many data fields as possible. Replace your name, birthday, billing information, email and physical addresses, and other fields with false information.

CONCLUSION:

Hope this long guide will help you secure your accounts online.

GOOD LUCK!

It has been suggested that the strongest password is the one you don’t know. Humans are notoriously poor at developing effective passwords because we are limited largely by the constraints of memory and the desire for convenience. Later

in this chapter I will teach you how to create effective, difficult-to-crack passwords that are still memorable and usable. I recommend you use a different username and password on all of your online accounts. This may seem terribly difficult,

exceedingly inconvenient, and impossible to remember, and generally I would agree. With only the benefit of human memory it would be nearly impossible to

remember and use more than just a few passwords of the recommended length

and complexity. For that reason, I’ve chosen to begin this chapter with a discussion of password managers, one of the single biggest and most important tools you can

employ to strengthen your digital security posture.

I have been using password managers for years, and there’s no way I’d even consider the possibility of going back to not using one. A password manager is a purpose-built application that creates an encrypted database for storing and organizing your usernames and passwords. Password managers solve many of the problems inherent in password development and use by “remembering” your passwords for you so that you don’t have to. This allows you to easily implement the online account best practices of using a different username and password on every one of your online accounts, using passwords that are randomly generated and of the maximum allowable length and complexity, and changing them as often as you deem prudent without fear of forgetting them.

Because password managers store all your passwords in one place, they create an “eggs-in-one-basket” situation. It should go without saying that a password

manager should be protected by an extremely strong password, and if at all possible, two-factor authentication (2FA). If you can only take the time to remember one

very strong, very complex password, you should do so for your password manager. Be especially careful not to lose or forget this password.

Password managers are designed to not let you back in without the correct authentication credentials. This could result in the loss of all passwords for all your accounts, an unenviable situation in which to find yourself. It should also go

without saying that your password manager should be backed up, frequently. If you are using a host-based manager and your computer crashes, you must have a

way to recover the information the password manager contained. Otherwise you risk being locked out of, and potentially losing, hundreds of accounts.

There are two basic categories of password managers, host-based and web-based. Although I will discuss both, my recommendation is to only use host-based

password managers. While web-based password managers are strongly encrypted, they are significantly riskier because they store your passwords in the cloud on machines that you do not personally control. Further, online password databases are a natural target for hackers because of the wealth of information they contain.

Though a certain amount of confidence is placed in all online account providers, an extraordinary amount is required to entrust your passwords to all your accounts to

an online service. I have not found yet an online service to which I am ready to give this level of trust for my extremely sensitive accounts, and frankly don’t believe I ever will.

HOST-BASED PASSWORD MANAGERS

A host-based password manager is an application that runs locally on a single device. All the information that is stored in a host-based password manager is stored only on that device and is not sent to the cloud or otherwise transmitted.This is somewhat less convenient than a web-based password manager as your passwords are only available on your computer or device. As a result, you may not

be able to log into your online accounts from computers other than the ones you own and that store your password database. This is not an issue for me since I’m

reluctant to log into an account from a computer that I don’t control and therefore don’t trust. However, there are good reasons to use a host-based password manager. The biggest advantage host-based managers enjoy over web-based

password managers is security. I have an instinctual, inherent distrust in cloud storage, and prefer to keep all my password, stored safely on my own devices .

QUBES OS: KEEPASSX

KeePassX is by far my favorite open-source host-based password manager for Linux machines, and it comes pre-installed on Qubes, on the Debian VMs. I recommend you create a new database on a VM labeled “vault” with KeePassX,

and to further enhance your security, store that database inside a hidden veracrypt container with a strong password. It’s as simple as downloading the .tar.bz2 file from the veracrypt website, decompressing it, and running a bash command on the folder to install veracrypt. If you’re having difficulty doing this, feel free to contact me and I will help you with that.

GLOBAL PASSWORD POLICIES

USERNAMES

With password managers to keep up with all of your login information, it is now possible to elevate your security posture significantly without a corresponding increase in the amount of work required. Generally, usernames are completelyoverlooked in the discussion of online security. I think this is a huge mistake. I believe that usernames should be considered the very first line of defense for such accounts. Most websites require at least two things to log in: a username and a

password. If the attacker cannot find your username, your account I significantly more secure. To launch an attack against your account would require first finding your account and an obscure username greatly reduces the chances of this

happening.

A predictable username has several problems, the first of which is susceptibility to guessing. If an attacker is targeting an attack against a specific individual, he or she will attempt to guess the target’s username(s) to various sites. The attacker will base guesses on known information about that person. This information can be gathered online from social media sites, personal blogs, people search sites, and public records. Predictable usernames are most commonly generated from a

combination of first, middle, and last names. For example, if your name is Amy Schumer your username might be “ABSchumer”. Sometimes they are combinations of monikers or initials and dates of birth such as “chumer81”. Once

the username has been discovered the attacker can now target that account and attempt to break the password. Conversely, the attacker can never begin targeting the account if it cannot be located.

The second problem with predictable usernames is that they are typically used across multiple websites, especially when the email address associated with the

account is used as the username. Using the same username across several of your accounts correlates those accounts. This makes them easier to locate and leaks

information about you such as your social media presence, interests, the online services and commerce sites you use, etc. This can expose a great deal of information about you. After locating your username, the attacker in this scenario

may use a service like Namechk (https://namechk.com/) to locate other accounts you have. If a common username and password combination are used across

multiple accounts, hacking one account can very quickly lead to the compromise of multiple accounts with disastrous consequences. Though you may not care if your throwaway email account or an old social media profile is hacked, it could lead to

your bank account or an active e-commerce account being hacked if they share a username and password.

The third major problem with predictable usernames is that when breaches occur, the username and password combinations are usually sold or posted online in massive databases. If you use a username or email address that correlates to your name, a breach can reveal personal information about you, especially if you have an uncommon name. As an example, let’s assume your name is Harrison Tang and your username to a site is harrisontang83, an obvious and easily guessable username based on your name and year of birth. Let’s also assume that a large

password breach occurs at a given site, and the usernames and passwords are posted online (which is very common by the way). Anyone seeing this database

would easily recognize your name and with some research could probably confirm the user is you. This reveals information about you and your personal interests. This could be a dating site (like Adult Friend Finder or Ashley Madison), a bank, an ecommerce site, or an online service of some sort. This would reveal to anyone

seeing this database that you use this dating site, bank, online retailer, or service,leading to further avenues of exploitation.

To combat this, you should consider the username a security measure. If the usernames on your accounts happen to be obvious, change them immediately. If a particular site does not allow you to change your username, consider closing the account and opening a new one using a non-obvious username. I’d personally consider a random-generated username for maximum anonymity. An ideal username would look something like this: 532T4VYL9NQ54BTMDZI1.

PASSWORDS

Though password managers provide most of the memory you need, there are still a handful of passwords that you will need to manually enter on a day-to-day basis. Not only do you want these passwords to be memorable, you also need them to be incredibly strong as the compromise of these passwords could lead to the compromise of all of your sensitive data. For this reason, you need to know how to develop a strong password that you can remember and enter manually.

PASSWORD BASICS: Before I discuss how to build a good, strong password it is critical to understand what comprises one. There are two factors that make (or break) a password: length and complexity. Added length and complexity both

exponentially increase the difficulty in breaking a password. Password length is uncomplicated. With today’s computing power, 20 characters is a prudent MINIMUM length (if your site does not allow a longer password). When passwords are cracked using brute force techniques, powerful processors run through hundreds of millions or billions of possible passwords per second. Every possible combination of a very short password could be tested in a matter of minutes with strong enough computing power, and computers are growing faster

every day. Password length is the single most important factor that increases the strength of a password. When using a password manager, we will use passwords that are much longer than 20 characters, sometimes exceeding 100. If this seems like overkill, consider the following. Regardless of whether a password is 1 character or 100, both

require the exact same amount of effort when using a password manager. Why not go with the longest allowable password? If a site with which you are registering does not allow a longer password, think twice before registering with

that service.

Complexity can be a bit trickier. Password complexity is created by following some basic rules. Ideally a password will contain characters from the full ASCII suite, including upper and lower-case letters, numbers, special characters

(!@#$%^&*_+=-/.,<>?;””:[]}{\|), and spaces. Spaces are very important as they are not commonly used in passwords, and as a result are not commonly searched for by password-cracking programs.

PASSWORD VULNERABILITIES: You may be wondering why such extreme measures are needed to develop an effective password. The reason complexity is desirable is that passwords are not typically cracked by “dumb” brute force methods alone, like starting at lowercase “a” and going all the way through “ZZZZZZZZZZZ”, and testing everything in between.

Though brute-force attacks exist, they are not the most popular or effective method of cracking a password, as they can take an immense amount of time. Time is the enemy of the password cracker, and your goal in designing a password should not be to make it unbreakable. Nothing is truly unbreakable given enough

time, but you should aim to make it take an unacceptable length of time.

Passwords are usually cracked in a much timelier manner by understanding how

people make passwords and designing a dictionary attack to defeat it. Dictionary

attacks rely on specific knowledge of the target and heuristics.

Knowledge of the target is useful when cracking a password because personal information is frequently used as the basis for human-generated passwords. An individual may use his or her birthday (or birthdays of a spouse, or children, or a combination thereof), favorite sports team or player, or other personal information or interests. This information can be input into programs like the Common User Password Profiler (CUPP). This application takes such tedious personal data as birthdays, names, occupation, and other keywords, and generates thousands of potential passwords based on the data. This list of passwords can then be programmed into a custom dictionary attack against the target machine or account.

Dictionary attacks work through a trial and error approach. First, a list of passwords is entered into a password-cracking program. This list might be customized against the target (through applications like CUPP as described above), or it may be more generic. Even though “generic” lists are not tailored to a specific target, they are still far more successful than they should be. These lists are based upon the heuristics of how people develop passwords. These lists are developed with the knowledge that many people use the techniques explained in the following list of password pitfalls.

o Never use a dictionary word as your password. Almost all dictionary attacks will include a list of dictionary words in a number of languages.

o Do not use a dictionary word with numbers/characters at the beginning or end (e.g. password11 or 11password), and do not use a dictionary word with simple obfuscation (p@ssword). These are the most common methods of adding complexity to a dictionary word-based password, and combinations such as these would be tested in any decent dictionary attack.

o Never leave the default password on your devices (Bluetooth devices and wireless routers are notable offenders in the retail market). Default passwords for any device imaginable are available through a simple web search and would absolutely be included in an attack against a known device.

o Never use information that is personally relatable to you. As I have discussed, information that is personally relatable to you can be used in an attack that is customized to target you specifically.

The inherent problem with complexity is that it makes our passwords difficult to remember, though with creativity it is still possible to create passwords that are very long, very complex, yet still memorable. Below are two of my favorite techniques to develop strong (and memorable) passwords.

THE PASSPHRASE: A passphrase is a short phrase instead of a single word and is my preferred technique. Passphrases work like passwords but are much more

difficult to break due to their extreme length. Additionally, if appropriate punctuation is used, a passphrase will contain complexity with upper and lower-case letters and spaces. A shrewd passphrase designer could even devise phrase

that contains numbers and special characters. An example of a solid passphrase might be the following.

“There’s always money in the banana stand!”

An even better example might be:

“We were married on 07/10/09 on Revere Beach”.

Both of those passphrases are extremely strong and would take a long, long time to break. The first one contains 43 characters, including letters in upper and lower-cases, special characters, and spaces. The second is even longer at 46 characters, and it contains numbers in addition to having all the characteristics of the first. Additionally, neither of these passphrases would be terribly difficult to remember.

DICEWARE PASSPHRASES: Diceware is a method of creating secure, randomly-generated passphrases using a set of dice to create entropy. To create a diceware passphrase you will need one dice and a diceware word list. Numerous diceware word lists are available online. Because of the way passwords are created, these lists do not need to be kept secret. These lists consist of 7,776 five-digit numbers, each with an accompanying word and look like this:

43612 noisy

43613 nolan

43614 noll

43615 nolo

43616 nomad

43621 non

43622 nonce

43623 none

43624 nook

43625 noon

43626 noose

After you have acquired a dice and a word list, you can begin creating a passphrase by rolling the dice and recording the result. Do this five times. The five numbers that you recorded will correspond with a word on the diceware list. This is the first word in your passphrase. You must repeat this process for every additional word you wish to add to your passphrase. For an eight-word passphrase you will have to roll the dice 40 times. Diceware passwords are incredibly strong but also enjoy the benefit of being incredibly easy to remember. A resulting diceware passphrase may look like the following. puma visor closet fob angelo bottle timid taxi fjord baggy Consisting of ten short words, this passphrase contains 58 characters including spaces and would not be overly difficult to remember. After you have completed this and compiled the words from the list into a passphrase you can add even more entropy to the passphrase by capitalizing certain words, inserting numbers and special characters, and adding spaces. Experts currently recommend that six words be used in a diceware passphrase for standard-security applications, with more words added for higher-security purposes. You should NEVER use a digital or online dice-roll simulator for this. If it is compromised or in any way insecure, so is your new passphrase. Wordlists are at https://theworld.com/~reinhold/diceware.html

THE “FIRST LETTER” METHOD: This method is a great way to develop a complex password, especially if it does not have to be terribly long (or cannot be because of site restrictions on password length). For this method select a phrase or lyric that is memorable only to you. Take the first (or last) letter of each word to form your password. In the example below, we use a few words from the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States. We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility

WtpotUSiotfampueJidT

This password contains 20 characters, upper and lowercase letters (the letters that

are actually capitalized in the Preamble are capitalized in the password), and does not in any way resemble a dictionary word. This would be a very robust password. The complexity and length of this password could be increased greatly by spelling out a couple of the words in the phrase, and more complex still by replacing a letter or two with special symbols as in the following example.

We the People of the United States, i02famPu,eJ,idT

Containing 51 characters, this is the strongest password yet, but would still be fairly easy to remember after taking some time to commit it to memory. The first seven words are spelled out and punctuated correctly, and the last fifteen words are represented only by a first letter, some of which are substituted with a special

character of number. This password is very long and very complex, and would take EONS to crack with current computing power.

OTHER PASSWORD ISSUES

Even if all your passwords are strong, there are some other issues to be aware of.MULTIPLE ACCOUNTS: Though this is covered elsewhere in this book it is worth reiterating. Each of your online accounts should have its own unique password that is not used on any other account. Otherwise the compromise of one account can lead quickly to the compromise of many of your accounts. If a password

manager is doing all the work for you there is no reason not to have different passwords on every single online account.

PASSWORD RESET MECHANISMS: Most online accounts feature a password

recovery option for use in case you forget your password. Though these are sometimes referred to as “security” questions, in reality they are convenience questions for forgetful users. Numerous accounts have been hacked by guessing

the answers to security questions or answering them correctly based on open source research, including the Yahoo Mail account of former Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin. The best way to answer these questions is with a randomly

generated series of letters, numbers, and special characters (if numbers and special characters are allowed). This will make your account far more difficult to

breach through the password-reset questions. If you use a password manager, the answers to these questions can be stored in the “Comments” section of each

entry, allowing you to reset your password in the event you become locked out of your account.

If you are prompted to enter a password “hint”, I recommend using purposely misleading information. This will send the attacker on a wild goose chase if he or she attempt to discover your password through the information contained in the hint. You should never use anything in the hint that leaks any personal information

about you, and if you are using a strong, randomly generated password, the hint should have nothing at all to do with the password itself. Some examples of my favorite purposely misleading hints might be: My Birthday, Miami Dolphins, Texas Hold’em, or Password, none of which have anything at all to do with the password at which they “hint”.

PASSWORD LIFESPAN AND PASSWORD FATIGUE: Like youthful good looks,

architecture, and perishable foods, passwords are vulnerable to the ravages of time. The longer an attacker has to work at compromising your password, the

weaker it becomes in practice. Accordingly, password should be change periodically. In my opinion, they should be changed every six months if no extenuating circumstances exist. I change all of my important passwords much

more often than that, because as a security professional, I am probably much more likely than most to be targeted (not to mention much more paranoid, as well). If you have any reason to suspect an online account, your wireless network, or your computer itself has been breached you should change your password IMMEDIATELY. The new password should be drastically different from the old one.

If you are using a password manager, a practice I strongly recommend, changing passwords is not difficult at all. Remembering them is a non-issue. If you choose not to use a password manager, or you have more than one or two accounts for which you prefer to enter the password manually, you may become susceptible to password fatigue. Password fatigue is the phenomenon of using the same four or five passwords in rotation if you change them, or are forced to change them, frequently. This impacts security negatively by making your password patterns predictable, and exposes you to the possibility of all the passwords in your rotation being cracked.

With modern password hashing techniques, changing passwords frequently is typically unnecessary. The corporate practice of requiring a new password every 30, 60, or 90 days is a throwback to the days when passwords were predominantly stored in plaintext and there was significant risk of the entire password database being hacked. If passwords are being stored correctly, they should be secure even when the database is breached. With that being said, I am more paranoid than most and regularly change my passwords on all of my important accounts. Though it takes a bit of time and patience to update passwords on multiple sites, doing a few each week in a constant rotation can ease the tedium a bit and ensures that if one of your passwords is compromised it will only be good for a few weeks at most.

TWO-FACTOR AUTHENTICATION

These days, one does not have to specifically follow security news to know that password compromises happen with shocking regularity. The Wired cover story about the hack on Mat Honan in late 2012 fully underscores the weaknesses in passwords. Mr. Honan is also an excellent case study in the folly of using the same password across multiple accounts. When one of his passwords was hacked, it ledto the compromise of several of his accounts. Passwords are becoming a weaker method for securing data. Passwords can be brute-force, captured during insecure

logins, via key-loggers, via phishing pages, or lost when sites that do not store passwords securely are hacked. There is a method of securing many accounts that offers an orders-of-magnitude increase in the security of those accounts: two-factor authentication(2FA).

Using 2FA, each login requires that you offer something other than just a username and password. There are several ways 2FA can work, and there are three categories of information that can be used as a second factor. The three possible factors are something you know (usually a password), something you have, and something you are (fingerprint, retinal scan, voice print, etc.). A 2FA scheme will utilize at least two of these factors, one of which is almost always a password.

PGP KEY MESSAGE DECRYPTION: With your account setup with a PGP key that you control setup as a second factor, you will enter your username and password to login. Before being allowed access to the account, you will be presented with an encrypted message, that was encrypted with your own PGP public key. Once you decrypt the message, a code will be given to you. Upon entering the code, access to the account will be granted.

Sadly, I have yet to seen a Clearnet website deploy this kind of security measure. The only websites that have this kind of protection in place are darknet websites and markets. Most likely because of the fact that most people don’t use PGP to communicate, if not on the darknet, so it is not a very popular security measure.

This is very unfortunate, as PGP key message decryption, is most likely the single best method to secure your account from hackers, and currently, my favorite.

With Qubes OS, we can create an isolated VM, with no access to the internet, especially designed for the use of PGP, which makes things extremely more secure.

I recommend you clone the fedora-26 TemplateVM into fedora-26-pgp and then simply create a new AppVM based on that template, to which you will then label it “pgp” and give it no access to the internet. From there, to use PGP it is as easy as setting up a new key pair and knowing the command line commands to

encrypt/decrypt messages. You can follow the tutorial in the link below to accomplish so.

https://apapadop.wordpress.com/2013/08/21/using-gnupg-with-qubesos/

TEXT/SMS: With this method, a code will be sent via text/SMS message to your

mobile phone. Upon entering the code, which is typically 6-8 digits, access to the account will be granted.

Using the text/SMS scheme of two-factor authentication is a major security upgrade but is not as good as the next option we will discuss: the dedicated authenticator app. Text/SMS can be defeated if your phone’s texts are forwarded to another number. This may happen if your service provider account is hacked, or if a phone company employee is a victim of social engineering and allows an unauthorized person to make changes to your account. This may seem like a very sophisticated and unlikely attack vector, but several well-documented cases of this

attack have occurred.

APP (APPLICATION): Another option for smartphone owners and Qubes OS users is a dedicated two-factor authentication app. One such app is the Google Authenticator. Others include

2FAS

FreeOTP

Aegis

With the app installed, you will visit the website and enter your username and password. Then, you will open the app, which will display a six-digit, one-time code for that account (this code changes every 30 seconds). You will enter the one-time code to login. Setup for the app is slightly more complicated than setting up text/SMS, but it is far from difficult.

Once the app is installed on your computer/phone, you visit the site for which you wish to setup 2FA. The site will give you a code that you can input on the app, which links your phone/computer to the account, and adds an entry for the

account into the app. Google Authenticator works for a number of sites, including Amazon Web Services, Dropbox, Gmail, Facebook, Microsoft, Wordpress, and more...

Though I generally consider app-based tokens more secure than text/SMS systems, it is important to be aware that they are not invulnerable. While an attack on your phone could get some of your login tokens, the capture of the token that is transmitted to your app could allow an attacker unlimited access to all your two-factor codes indefinitely. This is very unlikely however. In Qubes, you should create a VM specifically for this purpose ALONE, don’t use for nothing else, and don’t download or navigate the web in that VM. There are other VMs you can create specifically for those other purposes. Below is the link to a tutorial in setting up a VM on Qubes for this purpose.

https://www.qubes-os.org/doc/multifactor-authentication/

COMMON TO ALL: BASIC BEST PRACTICES

DO YOU REALLY NEED AN ACCOUNT? Many online accounts that you are asked to create are unnecessary and time-consuming. Some services require an account. Before you set one up, I strongly recommend considering the potential downsides. You should also carefully consider what data you are willing to entrust to a website. An online dating site may request a great deal of data and periodically, invite you to participate in surveys. Of course, it will also ask you to upload photographs. I urge you to use caution when doing so because it is a near certainty that any information you put on the internet will one day be compromised in some manner.

USE ACCURATE INFORMATION SPARINGLY: When signing up for a new online account, consider what information is really important and necessary to the creation of the account. When you sign up for an email account, does it really need your true date of birth? Obviously not. E-commerce sites require your address to ship packages to you, but do they need your real name? Perhaps they do. When you create an online account with your bank, do you need to use complete and accurate information? Yes, you most likely do, unless you are conducting any type of fraudulent activity.

CHECK THE STATUS OF EXISTING ACCOUNTS: An early step in securing online accounts is to ensure they have not been breached. There are a couple of services that will offer you a bit of insight into this by allowing you to cross-reference your email address against lists of hacked accounts. Breachalarm.com allows you to input your email address, which it then cross-references against a list of hacked accounts. If your account has been hacked, change the password immediately.

Haveibeenpwned.com is a similar website that checks both email addresses and usernames against lists of known-hacked accounts. The site is relatively new and maintains a database of breached accounts.

GET RID OF UNUSED OR UNTRUSTED ACCOUNTS: If you have old online accounts

that are no longer used, close them down if possible. Some websites can help you do this such as, AccountKiller(www.accountkiller.com), and Just Delete Me(

www.justdelete.me). Before closing an account, I highly recommend you get rid of as much personal information as you can in the account. Many services will continue to harvest your account for personal information, even after it has been closed. Before closing the account, login and replace the information in as many data fields as possible. Replace your name, birthday, billing information, email and physical addresses, and other fields with false information.

CONCLUSION:

Hope this long guide will help you secure your accounts online.

GOOD LUCK!